Following the successful PlayStation game of the same name (unleashed on gamers in 1999 and superseded by several sequels/spin-offs) Silent HIll continued a trend that brought in a few shillings for the film industry whilst simultaneously burdening the preciously limited time of viewers with an increasingly large and smelly mound of dung to wade through. Guilty entries in the sub-genre of computer game adaptations included House of the Dead, Alone in the Dark, Postal and, to a lesser extent, Resident Evil (although that series can be entertaining in a switch-your-brain-off manner). Back in the nineties it was rubbish like Street Fighter, Mortal Kombat (bearable maybe) and Super Mario Bros.; in the noughties it was the horror movie fan who became the target. I wrote off Silent Hill when I caught the theatrical presentation back in 2006: too long, not enough story, style over content, Sean Bean, etc. Despite that, however, it’s sometimes worth checking out a movie for a second viewing because it can reveal its underlying charms that way, should there be any present. I’ve since seen it around six times at the point of writing this.

Swapping Harry from the game for a woman (in fact that’s the case with many of the characters) called Rose, the storyline otherwise remains fairly faithful to the first game: Rose and her husband Christopher have a few problems with daughter Sharon whereby she sleepwalks, unconsciously draws up nasty little images and mumbles about a place called Silent Hill that they discover is a ghost town with a horrific history. Rose decides the only way to break the cycle (medication hasn’t worked) is to take Sharon off to this place Silent Hill to see why it’s become such an ongoing mental problem with the girl. After coming into unwanted contact with a policewoman along the way, Rose and the cop both crash their car and bike respectively, just outside of Silent Hill itself. Rose wakes up to find Sharon missing. She goes in search across the misty town, a place strangely misplaced from reality, and soon realises there’s something truly frightening about the environment. Air-raid sirens periodically announce the arrival of all-encompassing darkness, with it truly monstrous organisms that will slaughter anything vaguely human. Meanwhile Christopher is understandably perturbed by his wife’s rash trip with their daughter and heads off to Silent Hill himself. There he finds a police detective and team overseeing the scene of the former vehicle accident. Both the detective and Christopher head into the town to look for Rose and Sharon, but while they seem to be all there simultaneously, they don’t actually see each other: as Chris and the detective are present in everyday reality, Rose and the female cop now exist in some alternate dimension, a limbo world inhabited by hellish creatures and the damned former inhabitants of the town.

The story of this Canadian-French production is undoubtedly quite limited, with many sequences simply following Rose as she’s exploring the town or being threatened by demonic apparitions. The problem inherently lies with the very nature of the production, it being a game-to-film adaptation. A writer is damned if they do or don’t in that respect: add too much story and you’re at risk of disappointing the hardcore fans of the game by not maintaining faithfulness. Whereas, take the game literally and there’s inevitably barely enough story to stretch the onscreen action to conventional running time. In that respect at least Silent Hill falls into the sincere camp, but it still exceeds two hours and that’s way too long in my opinion. Dialogue is oddly dated in places, perhaps deliberately so in order to enhance the film’s affiliation with the unfamiliar (it’s hard to imagine that writer Roger Avary botched the job after his work on the likes of Pulp Fiction, True Romance, etc.) while logic is bizarre at times – despite the source I think this could have done with some work. The other issue I really have is with Sean Bean. Of course, he’s often extremely good at his vocation but he just doesn’t cut playing an American. If I was American I’d think he was taking the piss, it just doesn’t work. I never see much point in hiring an actor for a part that requires an accent so grossly at odds with their own natural tongue and here we have someone heavily northern (from Sheffield specifically) who can pull off a traditional English accent well enough, but when it comes to American he’s an embarrassment to whatever’s left of international peace.

On the positive side the film’s visuals are stunning and director Christophe Gans possesses stellar understanding of powerful composition, aided in no doubt by the vast, decaying production design of legendary Carol Spier - many of these frames could be frozen and hung on the wall (depending on the surrounding décor…), and the 2.35:1 proportions are comfortably put to use by the director and Danish cinematographer Dan Laustsen. Colour choices and contrasts are so acute it’s almost too perfect. Similarly, the music (mostly adopted from the game) adds to the tension with originality and creepiness throughout. Radha Mitchell does well as Rose, and though the Australian is another accent-choice anomaly she’s certainly more successful in this area than Bean. She also looks fantastic. Finally, the point of the film: terror. Certain scenes are utterly nightmarish in tone and effect, there are times when proceedings escalate to such a tremendous height of insanity and absolute ghastliness they not only drag you in but also make up for the movie’s aforementioned shortcomings. The inhuman creations that populate the world are imaginative, an appreciable cut above usual genre monsters. Whereas I once considered Silent Hill to be an overly stylistic waste of space I eventually changed my attitude to the film.

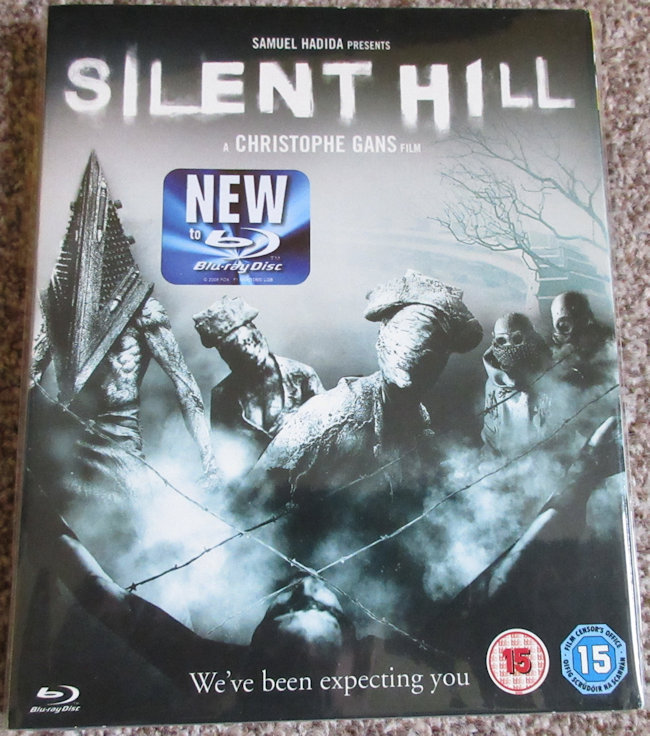

An early Blu-ray release (and purchase, for me) in the UK from Pathé, the disc (significantly better than the Sony US edition of the same period) has stood up surprisingly well over time – stark contrasts and colours over a substrate of apparent grain that looks okay in motion although doesn’t hold up quite so well under still-frame analysis. The reasonably pleasing image is combined with a powerful DTS HD MA Hi-Res audio track. There’s also a reasonable supply of extras. The same master was later utilised by Scream Factory for a special edition containing more extras and an overall higher bitrate (alongside slight differences in colour timing). Unless you’re desperate for the extras, I wouldn’t say that it’s worth upgrading. Perhaps more could be done with this 35mm (possibly Super 35)-shot film these days (although it was - as has become the norm - digitally mastered at intermediate stage, so that could limit possibilities if full remastering from the negative is not viable); if not, I’m happy enough with this disc.